How Trump and the Republicans can fix the CHIPS Act

The United States has a good thing going with the CHIPS Act but Trump and the Republicans could improve it.

The CHIPS Act represents a critical step toward securing America's semiconductor industry. But opportunities for improvement remain. While the Act has already shown promise in attracting major investments from chipmakers like TSMC and Samsung, targeted reforms could significantly enhance its effectiveness. This analysis presents a comprehensive framework for optimizing the CHIPS Act through three key mechanisms: strategic use of tariffs, regulatory streamlining, and additional support measures, including targeted Chinese semiconductor tariffs and a national chip reserve.

Introduction

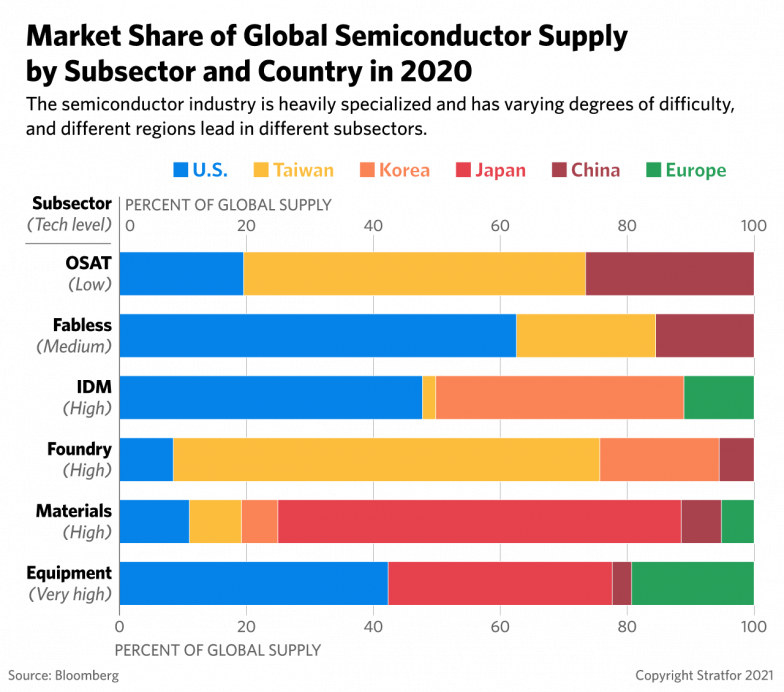

The semiconductor industry has become fundamental to both modern economic power and military capability. While the United States maintains dominance in areas like equipment manufacturing, chip design, and software, it lags in other areas. Most notably, semiconductor fabrication — the actual process of manufacturing chips — has largely moved overseas. This shift wasn't driven by comparative advantage or economic inevitability, but by historical policy decisions that now demand correction. In 1990, the United States represented 37% of global fabrication capacity. Today it represents around 10%.1 The CHIPS Act, which aims to bolster U.S. semiconductor fabrication capabilities, represents a necessary (though imperfect) targeted industrial policy intervention, with a goal of getting the United States back to a lean 20% of global chip production. The incoming administration has the chance to optimize its implementation.

There is an argument, frequently made by industry analysts, that semiconductor fabrication should be left to other nations as part of the global supply chain, with some even suggesting that Asian countries possess some inherent advantage in chip manufacturing. I remember seeing one online commentator point to “Confucian values” as a reason why industrial policy around chips will fail in America.

This argument falls apart under historical and economic scrutiny. Historically, the decision to outsource fabrication was as much about integration of East Asian allies into American supply chains as it was about any economic reality. From an economics perspective, much of the raw material for fabrication is already extant in the United States. American companies already manufacture most of the world's semiconductor equipment — the complex machinery required for chip fabrication. U.S. firms like Intel, Micron, and Global Foundries operate some of the world's most advanced fabrication facilities, consistently demonstrating American excellence in this sector. The notion that complex manufacturing requiring advanced engineering somehow cannot succeed in the United States contradicts both historical evidence and current reality. U.S. manufacturing remains the most productive on the planet.

More importantly, the strategic stakes are too high to accept this flawed logic. China is aggressively (unprofitably) subsidizing domestic semiconductor production, aiming to dominate the sector. That alone creates an untenable strategic vulnerability. Meanwhile, Taiwan, which currently houses much of the world's fabrication capacity, faces growing geopolitical pressure from China. With the risk of Taiwan falling under Chinese control, the strategic vulnerability becomes existential.

The CHIPS Act serves dual purposes: near-term national security, the need for which is outlined above, as well as long-term development of a resilient domestic semiconductor fabrication industry. While the United States dominates semiconductor design — with American firms like Broadcom, NVIDIA, Intel, and Texas Instruments controlling about 60-70% of the market — we've become dangerously, and perhaps inefficiently, dependent on overseas fabrication. Firms like Broadcom and NVIDIA make their chips in overseas fabs, primarily in Taiwan. While the United States dominates semiconductor design - with fabless American firms controlling about 60-70% of the market - we've become dangerously, and perhaps inefficiently, dependent on overseas fabrication. By taking back fabrication to America is not only strategically intelligent, it is sound economic policy, too, as it increases verticalization and reduces foreign dependency.

The primary challenge is financial. Fabrication facilities require massive capital investment, often in the tens of billions of dollars. These costs have historically deterred domestic construction. The CHIPS Act aims to bridge this gap, incentivizing both foreign and domestic firms to build in the United States.

Recent statements suggesting complete repeal of the Act have been misattributed to President-elect Trump. I am confident he has no interest in such a counterproductive action. But to the extent he has criticized the Act, then he and the new GOP majority in Congress should seize the opportunity to fix that which they deem broken by adopting three narrowly-tailored and linked reforms: (1) strategic application of tariffs based on successful precedents from the previous administration, (2) a strategic chip reserve, (3) streamlining regulatory requirements and thoughtful changes to the financial structure of subsidies (particularly “Notice of Funding Opportunity”, or NOFO clauses). These core improvements, supplemented by targeted yet massive tariffs on Chinese semiconductors and a strategic chip reserve, could significantly enhance the Act's effectiveness in achieving its stated goals.

The CHIPS Act and its Challenges

Industrial policy succeeds best when it pushes against something targeted.The CHIPS Act does exactly that, or at least it aims to. The fundamental challenge is that building semiconductor fabrication plants in the United States costs approximately 30% more than it does in Asia. The Act aims to bridge this gap, making domestic production economically viable. As we will see, though, the major problems with the act are overregulation and overreliance on subsidies.

I am going to unload a lot of criticism here but we should stay directionally positive. The CHIPS Act has indeed already shown promising results. TSMC and Samsung are building major fabrication facilities in the United States, with early reports suggesting the Arizona fab is achieving yields 4% higher than comparable facilities in Taiwan — though this data comes from early, limited production runs.2

To give a brief rundown of the bill, The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act, despite its awkward acronym, was enacted in August 2022. The Act allocated $280 billion over the next decade, with $52.7 billion dedicated to semiconductor manufacturing, research and development (R&D), and workforce development. An additional $24 billion provides tax credits to stimulate chip production, while $3 billion more supports wireless technology development.

China's aggressive moves in the semiconductor industry largely precipitated the CHIPS Act. The Chinese government is investing heavily to dominate the market for mature-node chips (25nm and above), targeting 50% market share by 2030. This strategy extends beyond mere self-sufficiency — it positions China to control global supply chains for everything from consumer electronics to military hardware. Combined with the risk of China seizing Taiwan's advanced chip fabrication capabilities, the threat has become too serious to ignore. You can read more about this in another article I wrote.3

The Act relies heavily on subsidies, and subsidy-like instruments, for driving investment and results. While subsidies are a necessary component of any serious industrial policy they cannot succeed alone. The Act needs additional mechanisms which can complement subsidies: tariffs, to protect these investments and ensure long-term commitment from firms, and a strategic chip reserve, to give firms a guaranteed income stream.

Additionally, the Act actually often counteracts the subsidies it relies on by forcing firms to comply with an extensive array of “everything bagel” regulatory requirements, from environmental to reporting to labor (and DEI for good measure). This slows down the distribution of funds and undercuts the subsidies through compliance costs.

The most painful regulation is the “NOFO” clause. Under this provision, “[r]ecipients receiving more than $150 million in CHIPS Direct Funding will be required to share with the U.S. government a portion of any cash flows or returns that exceed the applicant’s projections (above an agreed-upon threshold specified in the award).” Basically, the government can ask firms to return any revenue stream above a certain level if the government’s investment in that firm ends up being “too successful.”

A corollary of the regulatory burden is the slowness of fund distribution. Bureaucratic delays are killing the Act's momentum. Instead of rapidly deploying capital to accelerate domestic chip production, the program has become mired in administrative complexity. The fact that Intel, a key domestic producer, hasn't received any funding to date exemplifies this paralysis. This is particularly dangerous given the pace of global competition — Europe is investing $47 billion (with Germany adding another $20 billion) in semiconductor initiatives, while China is committing more than $300 billion to dominate the industry.

Let’s dig into the solutions: tariffs, chip reserves, and regulatory streamlining.

Tariffs as an Instrument

Tariffs are often dismissed by free-market purists as distortions that raise consumer prices and provoke retaliatory measures. This skepticism is understandable. However, when applied selectively to strategic industries, tariffs can ensure long-term commitment from foreign firms and protect the massive initial investments that domestic firms make.4 If you want to make the CHIPS Act subsidies successful, coupling them with tariffs is needed. We can see this with two examples tariffs from the first Trump administration, plus a historical example from the 1980’s in the semiconductor industry.

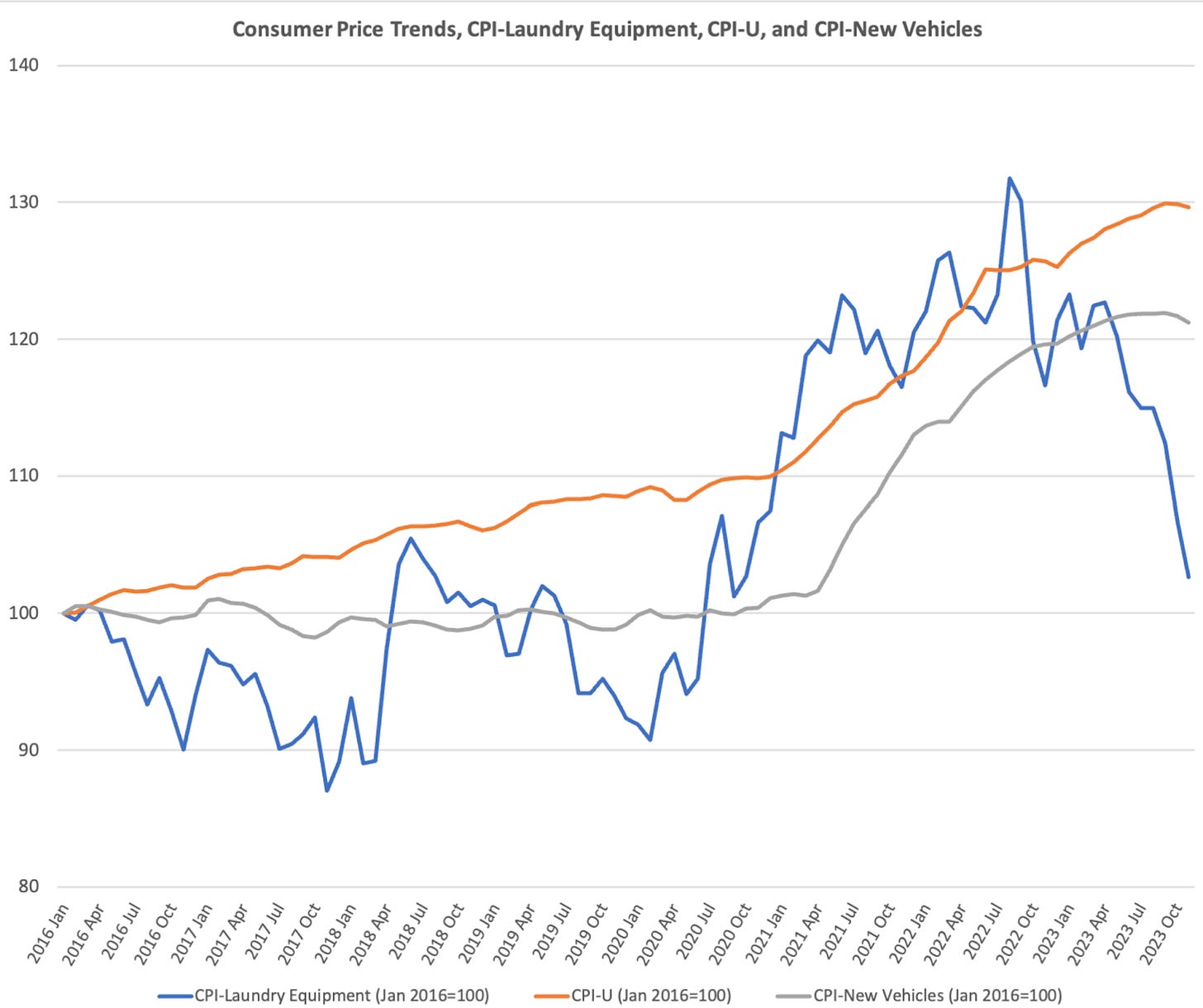

While not universally successful (the general tariffs across manufacturing and agriculture produced mixed results)5 Trump’s strategic tariffs from the first term did achieve some measure of success for narrow industries, particularly those on washing machines and steel. The washing machine tariffs are an example of getting foreign firms to behave well. And the steel tariffs are an example of protecting net new domestic manufacturing investments. Both of these are things we would want coupled with subsidies.

Washing machines provide an informative case study about how to get foreign firms to invest the way you want and how to protect them while they do so. These targeted and strategic tariffs, implemented in January 2018, ranged from 20% to 50%. The tariffs triggered significant “tariff-jumping investment,” with both Samsung and LG establishing major U.S. manufacturing plants to avoid import duties. Samsung invested $380 million in South Carolina and LG invested $360 million in Tennessee, each creating around 1,000 jobs. Contrary to concerns, washing machine prices quickly stabilized as these new plants began production (as seen below).6

The steel tariffs offer another instructive example of protecting domestic investment. After Trump imposed 25% tariffs in 2018, U.S. Steel and Nucor committed over $5 billion to modernizing their domestic facilities. Without protection from cheap imports, these massive capital investments in more efficient blast furnaces and electric arc facilities would have been too risky. Just as with washing machines, critics warned of devastating price effects, but the tariffs succeeded in their core goal - protecting the substantial investments needed to upgrade American steel production capacity.

The semiconductor sector's own history with tariffs, particularly the U.S.-Japan DRAM conflict of the 1980s, offers crucial lessons for today's competition with China. Japan had emerged as a dominant force in DRAM (Dynamic Random Access Memory), slashing U.S. market share from 70% to 20% by 1986 through better manufacturing and aggressive pricing. When Japan failed to honor initial agreements to stop chip dumping, the U.S. imposed 300% tariffs. While some dismiss this intervention because Intel soon pivoted to microprocessors, the tariffs achieved their goal — they saved America's DRAM industry. Micron not only survived but thrived, eventually capturing 20% of Japan's domestic market.

These historical examples suggest two ways to strengthen the CHIPS Act:

First, Trump can use lighter tariffs on all foreign produced chips (in the 10-20% range) as a protective measure to augment subsidies. These can protect domestic chip production as it ramps up and give proper incentive for foreign firms to invest, creating the same "tariff-jumping investment" effect we saw with washing machines.

The DRAM story shows how tariffs can be a cudgel. Trump can ensure TSMC and Samsung complete their investments through the potential threat of punitive tariffs if they do not. A credible commitment to this policy will prevent companies from abandoning their investments midway through.

Strategic Chip Reserves: Guaranteeing Demand and Security

A strategic chip reserve was considered during Trump's first administration but never implemented. While this proposal might seem unconventional, it serves both immediate national security needs and longer-term industrial strategy goals.

The national security case is straightforward. By maintaining stockpiles of critical semiconductor components, the government could ensure continuity of defense systems and critical infrastructure during supply disruptions. Recent shortages have demonstrated how vulnerable our military and industrial base are to semiconductor supply chain interruptions. A strategic reserve would provide a buffer against both short-term disruptions and potential geopolitical crises, particularly any involving Taiwan.

The industrial strategy benefits are equally compelling. By tying access to reserve contracts to specific domestic production targets, the government could provide semiconductor manufacturers with guaranteed demand — effectively creating a stable revenue floor for new facilities (one could even imagine that a revenue stream might be better for some firms than a subsidy). This approach has historical precedent in other strategic industries. The Strategic Petroleum Reserve, for example, helped sustain domestic oil production during market downturns. Similarly, defense procurement contracts often include minimum purchase guarantees to sustain critical manufacturing capabilities.

The reserve's composition would need careful consideration. Military and industrial applications require a broad spectrum of semiconductors, from advanced logic chips to mature-node analog devices. Defense systems often rely on specialized chips that may be several generations behind the cutting edge, while industrial control systems frequently use robust, proven designs rather than the latest nodes. The reserve would likely need to maintain stocks of both advanced logic chips (7nm and below) for modern weapons systems and mature node chips (28nm and above) for industrial and legacy military applications.

Implementation could follow successful models from other strategic reserves:

Long-term contracts with domestic producers to ensure steady supply. We could even have the reserves held by the suppliers, rather than the military itself.

Regular rotation of inventory to prevent obsolescence. Chips depreciate.

Geographic distribution of storage facilities to reduce vulnerability.

Coordination with industry to align stockpile composition with critical needs.

Regular assessment and updating of reserve requirements as technology evolves.

While specific quantities and exact composition would require detailed analysis by semiconductor experts and defense planners, the strategic value and the value as a complement to the CHIPS Act is clear.

The CHIPS Act Needs Streamlining

The CHIPS Act's implementation has become unnecessarily complex, undermining its strategic purpose. Effective industrial policy requires rapid, directed action — getting capital to firms quickly to achieve specific strategic goals. To an extent, you just need to shovel money at people — but while the Act's subsidies try to drive domestic semiconductor production, excessive regulation and government risk-aversion have created bottlenecks in disbursement and reduced the subsidies' effectiveness. The regulatory burden functions as an implicit tax, offsetting the very cost advantages the subsidies aim to create. Here are just a few examples, but the list could go on.

The first major obstacle comes from excessive financial and technical disclosure requirements. These force firms to reveal sensitive operational information that many are unwilling to share. SK Hynix has explicitly refused to apply for CHIPS funding due to these disclosure requirements, and Taiwan's national security laws may prevent TSMC from fully complying. The requirements create particular concern around intellectual property protection, with firms worried about revealing proprietary manufacturing processes and future product development plans.

Environmental compliance represents another significant barrier to rapid implementation. Environmental questionnaires and reviews typically delay groundbreaking by 6-12 months, while NEPA compliance alone adds approximately 5-10% to total project costs. The problem is compounded by multiple layers of environmental review, with state-level environmental regulations often duplicating federal requirements.

The Davis Bacon Act wage requirements create a third layer of regulatory burden. These requirements oblige firms with federal contracts over $2,000 to track and document compliance across their entire contractor network, adding significant paperwork and reporting costs. The Department of Labor's reporting requirements further complicate implementation, requiring dedicated compliance staff and creating additional overhead.

Perhaps most problematic are the NOFO (Notice of Funding Opportunity) provisions. The Act's "upside sharing" requirement forces companies receiving over $150 million to share an undefined portion of profits that exceed their projections. This intentionally vague profit-sharing threshold creates significant uncertainty for firms planning major investments. The provision effectively penalizes successful execution and innovation, while creating a perverse incentive for companies to overstate their initial projections to avoid triggering the clause. While we might want to restrict dividends for CHIPS Act grantees, this mechanism transforms what should be straightforward subsidies into a complex profit-sharing arrangement that discourages the very success the Act aims to achieve.

The regulations above, as well as many more, simply put, need to be cut out from the Act. They are counterproductive and injurious. Rather than facilitating rapid domestic semiconductor expansion, they create delays, add costs, and discourage participation from key industry players.

Big Nasty China Tariffs

The last suggestion I have is slightly tangential to the CHIPS Act, but is a necessary addition. China's growing presence in the U.S. semiconductor market poses a strategic rather than purely economic threat. As China aggressively expands its chip production capabilities, particularly in mature-node semiconductors, it threatens to create dangerous dependencies in America's hardware supply chain.

The solution requires decisive action: implementing extraordinarily high tariffs — up to 300% — on Chinese semiconductor imports, up from around 50%, where they are today. This isn't about protecting domestic industry from fair competition; it's about preventing a strategic adversary from establishing control over critical technology components. China's strategy is clear: Flood the market with mature-node chips, establish market dominance, and create U.S. dependence on Chinese suppliers. They're particularly targeting the high-node, less advanced chip market — components that, while less sophisticated, remain essential for industrial and military applications.

While the CHIPS Act's incentives and the proposed strategic chip reserve could help offset any market disruptions from such aggressive tariffs, that consideration is secondary. The primary goal must be to create a complete break from Chinese semiconductor dependence before it becomes entrenched.

Conclusion

The CHIPS Act represents a crucial first step in rebuilding America's semiconductor fabrication capacity, but its current implementation threatens to undermine its own goals. The solutions proposed here — strategic tariffs, regulatory streamlining, and additional support measures — would transform the Act from a well-intentioned but bureaucratically hampered program into an effective engine of industrial revival.

Perhaps most critically, these reforms would work together synergistically. Tariffs protect investments enabled by streamlined subsidies, while guaranteed demand from the strategic reserve provides long-term stability. Meanwhile, aggressive tariffs on Chinese semiconductors would prevent strategic vulnerabilities from developing while these domestic capabilities are built.

The global race for semiconductor independence is accelerating. Europe is investing heavily, and China is pouring hundreds of billions into domestic production. America cannot afford to let bureaucratic complexity and half-measures undermine this critical industry. With these targeted reforms, the CHIPS Act can fulfill its intended purpose: securing America's technological independence and industrial strength for decades to come.

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/the-chips-and-science-act-heres-whats-in-it

https://www.tomshardware.com/tech-industry/semiconductors/tsmc-arizona-fab-delivers-4-percent-more-yield-than-comparable-facilities-in-taiwan

noah has a good point about how currency fluctuations make general tariffs less effective than strategic tariffs on a certain set of industries.

Autor, D., Beck, A., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2024). Help for the Heartland? The Employment and Electoral Effects of the Trump Tariffs in the United States (NBER Working Paper No. 32082). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w32082

https://prosperousamerica.org/economic-view-tariff-jumping-investment-the-success-of-the-2018-washing-machine-tariffs/

I took the referral from Noah Smith and read this piece and agree, it's excellent. I recently read Chip Wars, so much of this was familiar terrain and complemented that work nicely. I think there are many centrist Democrats like me that can agree that the "everything bagel" approach is counterproductive. Interesting tidbit: I worked in US Customs as a Commercial Import Operations Specialist in the Port of San Francisco in the 90's. I spent many a Saturday in the office, on overtime pay of course, redlining invoices that contained Korean DRAMs in order to ensure that anti-dumping duties were assessed against Hynix and LG, and at the time it was debatable whether or not any good was coming from that effort, 90% of which happened in my office (being the closest port to Silicon Valley). I suppose me and my millions of dollars of revenue collection into the Treasury (minus a $50k annual salary for me) would be summarily executed by the DOGE ignorami of today. Anyway, anti-dumping aside, I think a more productive example of how tariffs CAN work is that, in the early 90's, imports of computer "parts" were free of duty, and imports of completed computers were assessed a duty of 3.7% of import value. This setup incentivized a broad and thriving industry (in the Bay Area and Texas at least) of computer assembly in the US, much of which I personally witnessed as a visiting federal officer. All of that left for China and elsewhere over the next few years, as a result of the ITA (Int'l Telecomms Agmt of '97), which made most tech products duty-free. I don't pretend to know if that production and jobs would have left anyway; I only know that it did. (Much like auto and NAFTA before it, in '93.) In contrast to the conventional wisdom at the time, hindsight is clear that allowing China into the WTO (another accomplishment of the 90's, successor to the GATT) was a huge mistake, as democracy did not accompany capitalism, and so instead of evolving into another EU-type of mostly peaceful trading partner, they are part of the global shift toward autocracy.

I'm really surprised at the highlight around the washing machine tarrifs as I believed the general consusus was that the data showed it to be incredibly inefficient. The cost per job was north of $800k for the consumer cost with the tarrifs in place dramatically increased prices, and once they were expired prices dropped.

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/higher-prices-extra-jobs-lessons-from-trumps-washing-machine-tariffs-185047360.html

This work around USA ship industry shows how often industrial policy only creates industry that can succeed while protected or subsidized and not competitive on its own.

https://www.construction-physics.com/p/why-cant-the-us-build-ships