Why Taiwan Matters (Actually), Part I

Part 1 of a 2 part series on why Taiwan matters and what the implications of the conflict actually are. The first part, here is a non-fiction. The second part is a sort of fiction.

This is a two part series on the conflict between the United States and China over Taiwan, a topic that I acknowledge has been quite exhaustively written about. I thought I’d do a nice twist on the genre. Part I is non-fiction and sets up the second part, a fictional sort of alt-future-history, extended into the future.

Part I will discuss the nature of the conflict over Taiwan, to show that it is primarily a conflict over regional hegemony. It will then discuss what are the best strategic options for the United States. Part II is a fictionalization of what might happen if we fumble the ball on that strategy.

Introduction to Part I

Let’s establish, what I believe, to be the main crux of the argument: Countries desire to be regional hegemons. It is a lucrative and powerful spot to be in. It’s good to be the king. Being the regional hegemon of East Asia gives you a springboard to global hegemony. It’s a natural desire for China, with great historical precedent, and it is the main reason for China’s quest to take Taiwan.

China’s goal in taking Taiwan is to retake the mantle of regional hegemon. Taiwan is simply a Schelling/focal point about which regional hegemony and signals of credible commitment now revolve, creating a mechanism to show that the United States’ security architecture is not relevant—effectively removing the competing power in the region.

Conversely, the United States has long adhered to a foreign policy of preventing the rise of a hostile hegemon in East Asia or Europe, understanding that such dominance would expose its strategic flanks. China’s drive for dominance is therefore pitted against America’s longstanding role as a regional balance. In response to this assertion of Chinese power, the United States has made its own military strength the backstop and foundation stone for an anti-Chinese regional coalition (in Elbridge Colby’s terminology, an anti-hegemonic coalition).

China is currently threatening the regional architecture of East Asia, which places the United States as a counterweight to its ambitions. Apart from the barebone realities that define such a contest—military power projection and economic power—the United States and China both face choices, responses, risks, and rewards to manage. The evolution of this contest could result in a variety of outcomes, ranging from a vague reset of the status quo (a “grand compromise”) to a more pessimistic “China Triumphant.”

While I do believe that regional hegemony underpins China’s ambitions in Taiwan, two other plausible explanations for its focus on Taiwan are often cited: chips (e.g., TSMC) and “national unification.” These arguments are ultimately not convincing.

China’s domestic chip capacity, including lower-node chips, is advancing significantly. It could achieve technological dominance without risking a military invasion of Taiwan. National unification and domestic causes are certainly more convincing than any others, but if China wanted national unification, they would be doing quite a bit differently.

Another meta-argument is that China is not an expansionist power and only seeks to “reunite” Taiwan, consistent with a national policy rather than regional domination. This is patently false. China has been the regional hegemon in Asia almost continuously since the Han. When its dominance was unimpeachable, few challenged it. When it was not, China historically acted—often forcefully—to reassert control.

Why be a regional hegemon?

The allure of regional hegemony extends far beyond mere prestige—it is about power, security, and economic domination. It’s the foundation stone for achieving global hegemony.

The United States’ rise as the undisputed regional hegemon in the Americas during the 19th and early 20th centuries offers a nice blueprint. The United States established a distinctly American form of dominance over its weaker neighbors—sometimes beneficent, sometimes coercive.

Neighboring countries like Mexico and Cuba became economically reliant on the United States, supplying raw materials while importing U.S. manufactured goods. This dynamic fueled the United States’ industrial expansion. Crucially, the regional security this dominance provided served as a springboard for the United States to project power globally. No competitors in the region meant they could look further afield.

China’s strategy in East Asia is no different. Unlike Latin America during the United States’ rise, which primarily supplied raw materials, East Asia is home to established industrial economies (and plenty of raw materials, like those in SE Asia) that both compete with and depend on China’s manufacturing dominance. China can both extract resources but also integrate regional economies into its industrial and trade networks, barrier free.

For China, the path to achieving regional hegemony runs through Taiwan, a linchpin with immense symbolic and strategic value. Taiwan is not only a challenge to the United States’ credibility but also a decisive test for the anti-hegemonic coalition in the Indo-Pacific. Successfully taking Taiwan would deliver a crippling blow to this coalition, discrediting the United States’ ability to defend its allies and uphold its security commitments. Such a failure would erode trust among regional partners like Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines, undermining the collective resistance to Chinese dominance.

Taiwan’s fall might trigger a bandwagoning effect, where states realign with the dominant power to secure their interests, allowing China to reshape the regional order to its advantage. Taiwan represents the fulcrum for consolidating Beijing’s regional supremacy.

Taiwan is not merely a territorial dispute, an issue of national pride, or a matter of semiconductor production. Instead, it is the centerpiece of China’s strategy to reset the historical order and secure its future as a global superpower.

Chips are not the goal

First, let’s consider the notion that China’s potential conquest of Taiwan is primarily driven by a desire to acquire advanced semiconductor technology, particularly from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). The main reason this argument falls short is that it overlooks China’s substantial investments in developing its own domestic chip production capabilities.

China has been aggressively investing in its semiconductor industry to reduce reliance on foreign technology and enhance self-sufficiency. In 2024 alone, China allocated approximately $41 billion to wafer fabrication, marking a significant increase from previous years. Leading Chinese companies, such as Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) and Hua Hong Semiconductor, are spearheading these efforts. Beyond SMIC, China has also been expanding its domestic semiconductor equipment manufacturing sector, with firms like Naura Technology Group—China’s largest semiconductor equipment manufacturer—making significant strides. These companies are steadily advancing their capabilities and are on track to achieve technological parity with TSMC, including the ability to produce chips using EUV (extreme ultraviolet) lithography.

Given these substantial investments and developments, it is implausible that China would undertake the immense risks associated with a military invasion of Taiwan solely to acquire semiconductor technology. If semiconductor access were truly the goal, China could negotiate a deal with Taiwan over independence in exchange for this technology—a far less risky and more practical approach.

National Unification and Nothing More is Not the Goal

The assertion that China's interest in Taiwan is solely about national unification, without broader ambitions for regional hegemony, is simply ahistorical hogwash. Throughout its history, China has engaged in both direct territorial expansion and the establishment of hegemonic influence over neighboring regions.

China has, quite to the contrary, used violent coercive force, sometimes invasion, sometimes simple threats of force, to expand its own directly ruled territorial boundaries and, far more often, draw neighbors into a regional hegemonic order, often called “The tributary system”. Additionally, in a not so surprising historical observation, whenever Asia became more competitive among national polities, China has become more aggressive and expansionist. The Qing seem to have quite the record of violent invasion of their neighbors.

Let’s start actual territorial expansion through history, since that one is seen as rarer. A map might help show the silliness of the “only national unification goal”. The Han Empire’s borders are on the right (note Vietnam) and the Qing’s borders are on the left.

I am not a geography expert, but this does look like territorial expansion. Such territorial expansion was a consistent feature of Chinese history, especially in the Qing. To list a few:

Southern Expansion: Various Chinese dynasties extended their control southward, often into regions like Northern Vietnam. For instance, during the Ming Dynasty, China launched invasions to assert dominance over Vietnam.

Central Asian and Mongolian Campaigns: China's historical expansion also extended into Central Asia and Mongolia. The Tang Dynasty notably expanded control into Central Asia, reaching as far as present-day Kazakhstan. This expansion was marked by significant military campaigns, including the Battle of Talas in 751 AD, where Tang forces confronted the Abbasid Caliphate.

Qing Dynasty Conquests: The Qing Dynasty expanded China's territories into areas such as Manchuria, Xinjiang, and Tibet, frequently through military conquest. These expansions were driven by strategic and security considerations, aiming to consolidate China's influence over vital frontier regions.

Beyond direct territorial control, China has historically sought to establish a hierarchical regional order. This system positioned China as the central authority, with neighboring states acknowledging its supremacy in exchange for political legitimacy and economic benefits (such as the right to trade in China).

While some narratives portray this arrangement as a harmonious Confucian order, it was just a brutish regional hegemony under a different name. This arrangement allowed China to exert significant influence over its neighbors' political and economic affairs, ensuring a regional hierarchy that favored Chinese interests.

The so-called tributary system was less about mutual respect and more about consolidating China's regional supremacy, with Confucian ideals serving as a veneer for realpolitik strategies. And China has used force to maintain this system, many many times (many more times than it used force for territorial expansion). Korea and Vietnam, which fell in and out of under direct Chinese territorial influence and indirect rule, are the biggest “beneficiaries” of this sort of violence:

The Ming and Qing in Southeast Asia: The Ming invaded Vietnam in the 1400s as punishment for Vietnam’s attempts to conquer Champa and installed a puppet dynasty to enforce control. China used veiled threats just as often, for example, warning Thailand and the Majapahit against attacking the Malacca Sultanate, placing Malacca under Chinese protection as a protectorate. The Qing invaded Burma and Vietnam several times.

The Ming and Qing in Korea: The Ming don’t invade Korea to conquer it per se, but instead act to maintain a puppet relationship with them by protecting them from a Japanese invasion. The Qing however, do just straight up invade.

Often you hear critics of the idea of “aggressive China” look at this data and point out that China fights relatively few wars vs. their Western counterparts. This might seem to be the case. After all, Europeans conquered entire continents. This overlooks the fact that its overwhelming dominance often precluded the need for frequent military interventions. The mere presence of China's power served as a deterrent, ensuring compliance from neighboring states without the necessity of force. But when it needs to fight, it does.

It’s not that, as is often claimed, the historical record exonerates China from accusations of territorial and hegemonic ambitions, making Taiwan just an “Internal affair”, it does quite the opposite.

State of Play

Now that we understand the stakes, what can the United States do about it? How does this all play out? Chinese regional hegemony would be a net negative for the world. While the United States is an imperfect democracy, it has promoted free trade and liberalization across the globe. In contrast, China is an autocracy that seeks to crush dissent and, just speaking purely of self interest, likely deny the United States economic access to East Asia if it achieved dominance.

A lot of foreign policy thinkers want to give agency to the United States, but the truth is that the United States is the acting global hegemon, defending an increasingly embattled position. The United States can do a lot, but in many ways, it is white (China) to move and we are responding to whatever they do next.

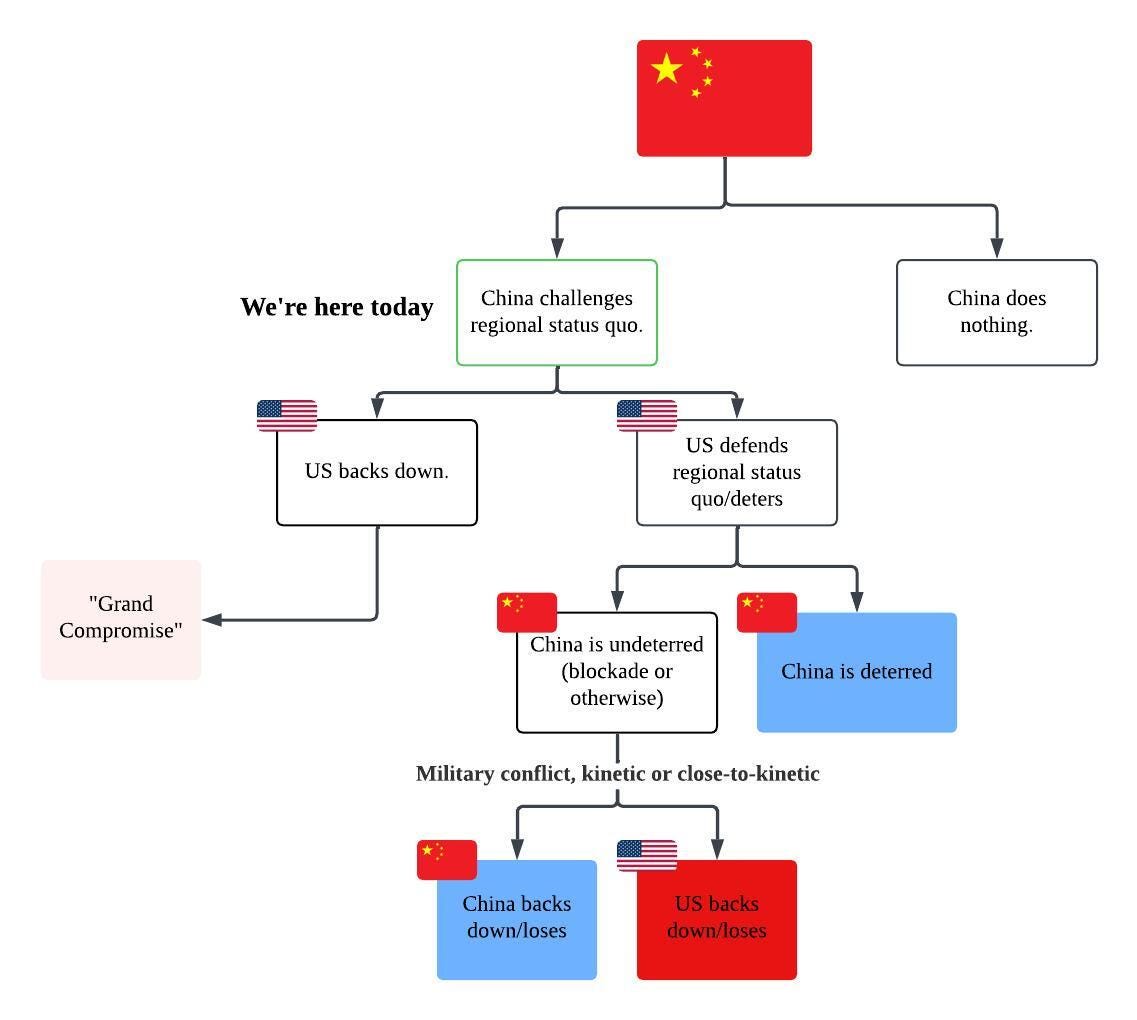

I’ve created a nice handy chart to help try to conceptualize all the possible outcomes and choices.

To conceptualize the possible outcomes and choices, I’ve created a framework based on the interactions between China and the United States. China faces three key decisions, while the U.S. has two. Together, these choices lead to four potential outcomes.

The Choices

Choice 1 (US), Defend or Compromise: The United States must decide whether to defend the status quo or compromise with China. Backing down would involve negotiating a “grand compromise” with Beijing, conceding significant influence in the region, but still having something left to show for it. Defending the status quo, on the other hand, would mean deterring China through measures such as weapons sales to Taiwan and strengthening the existing security architecture in Asia.

Choice 2 (China), Be Deterred or Attack: If the United States chooses to deter, China must decide whether to maintain the status quo or escalate toward a kinetic solution. Choosing deterrence would mean accepting that regional hegemony is unattainable. Opting for military action, however, is a high-risk strategy that could result in achieving regional dominance if successful.

Choice 3 (Mutual), Who Will Back Down:If a conflict arises, both sides face the ultimate decision of whether to back down. In a war between two nuclear-armed powers, it is unlikely that either side could deliver a decisive defeat, but eventually, one must concede. This concession could occur due to economic strain, military stalemate, or a fait accompli. The forms of conflict could range from a blockade to an amphibious invasion, each with varying degrees of escalation and consequences.

Possible Outcomes

Outcome 1, Grand Compromise: If the United States determines that China cannot be deterred and that a war would be too painful, risky, or unwinnable, the best option may be a “Grand Compromise.” While imperfect, the U.S. has compromised with authoritarian regimes before, as seen in the post-World War II division of Europe with the USSR. This outcome would likely leave Southeast Asia within China’s sphere of influence, Taiwan under Chinese control, and the U.S. maintaining a military presence in Korea and Japan. The specifics of the compromise would determine whether it ultimately favors one side more than the other.

Outcome 2, China Deterred: This outcome is the least disruptive to the world order. The United States successfully signals its permanent economic and military presence in the region, deterring China from further aggression. This buys the U.S. time to rebuild its military capacity and wait for China to potentially enter a secular decline (don’t bet on this one, friends). Regional stability is preserved, at least temporarily.

Outcome 3, US or Chinese victory: If war occurs, the victor will shape the region's future.

U.S. Triumphant: A decisive U.S. victory would restore the status quo ante bellum, reinforcing the existing security architecture that has underpinned peace and stability in East Asia for decades. It would reaffirm the United States’ commitment to its allies and its role as a global leader.

Chinese Triumphant: A Chinese victory would dismantle the current regional order, establishing Beijing as the unchallenged hegemon in East Asia. This outcome would represent a fundamental realignment of global power dynamics, signaling the decline of U.S. influence and ushering in an era of authoritarian dominance. It would be a grim future for the liberal world order.

Conclusion

The United States should prioritize deterrence as the best strategy to preserve the status quo and avoid catastrophic conflict. However, if military defeat appears likely, pursuing a grand compromise may be a better alternative than engaging in unwinnable war. The grand compromise outcome might seem un-American, but it might be the only available, depending on how things unfold. Even a military victory would likely be pyrrhic, resulting in heavy losses and would almost certainly set the stage for future conflicts.

This is a two player game afterall, so for China too, direct confrontation carries significant risks. Failure in a military campaign could be devastating. It will all come down to how strong China thinks it is (perception of strength vs. reality does often have a delta, especially for authoritarians). While Beijing might prefer a grand compromise if it guarantees meaningful gains, the lure of decisively reshaping the regional order could still push China toward escalation if leaders perceive a high probability of success.

The United States must act on two levels:

Immediate Actions: Invest in more deterrence based military capabilities, so as to create an asymmetry with China, strengthen alliances with Japan and other pivotal players, and secure critical supply chains through onshoring.

Long-Term Strategy: Accurately assess the balance of power, anticipate shifts in regional dynamics, and align policies to manage risks and opportunities effectively.

The ramifications of screwing this up are massive. And that’s what part 2 is all about. In Part 2, I will delve into a speculative "history of the future," taking the perspective of a historian in 2040, reflecting on a world where China emerged triumphant. This imagined retrospective will explore how China's victory over Taiwan set the stage for its rise as the unchallenged regional hegemon and the ripple effects that reshaped the global order.

Love this!